The Day of the Dead celebration is a unique way Mexicans embrace

death, distinct from other cultures.

For several days, festivity and ritual honor loved ones and relatives whose souls, as tradition holds, return for a night to reunite

with the living. It all begins at the end of October, continues through November 1st, dedicated to the souls of children, and culminates on

November 2nd, in remembrance of the spirits of adults.

Them and welcome them on their return to the earthly world

to share with the living, altars full of colors, flavors and smells are set up:

marigold flowers, sugar and chocolate skulls, bread of the dead, water,

candles, fruit, wine, mole and all the favorite food and drink of our ancestors.

The Day of the Dead

has its origins in the indigenous roots of the indigenous cultures of Mesoamerica, according to historians, to merge with Catholic

beliefs and give rise to a holiday that continues to evolve with the passage of time.

The cult of death was common among pre-Hispanic cultures. When someone died, they were buried wrapped in a mat and their

relatives organized a party in order to guide them on their journey to Mictlán.

(According to the Great Nahuatl Dictionary, mictlan means “hell” or “place of the dead,” where those who died natural or common

deaths arrived after a process that took four years.

Pre-Hispanic peoples also placed offerings

(food they liked, marigold flowers that lit their way, among others) in their rituals. For these cultures, death was part of a cycle and

the fate of the dead was marked by the way of life that the person had.

With the arrival of the Spaniards, other elements and practices were incorporated that are a reflection of the syncretism between

two cultures: the worldview of indigenous peoples and the religious beliefs of Catholicism.

THE INTERESTING THING ABOUT THIS CELEBRATION IS TO REMIND YOU HOW VALUABLE LIFE IS.

“The Europeans put some flowers, crayons, candles, and candles; the indigenous people added the incense with their copal and

the food and the marigold flower (Zempoalxóchitl),” says Mexico’s National Institute of Indigenous Peoples (INPI).

Historian Héctor Zarauz, author of the book “The Feast of Death”, highlights other elements that were added during the conquest.

“The crosses, which are representations of Catholicism, or some drinks that are added to the offering for the dead, distilled drinks

more that didn’t exist before. Nor is what is very traditional today, the bread of the dead, since at that time there was no flour.”

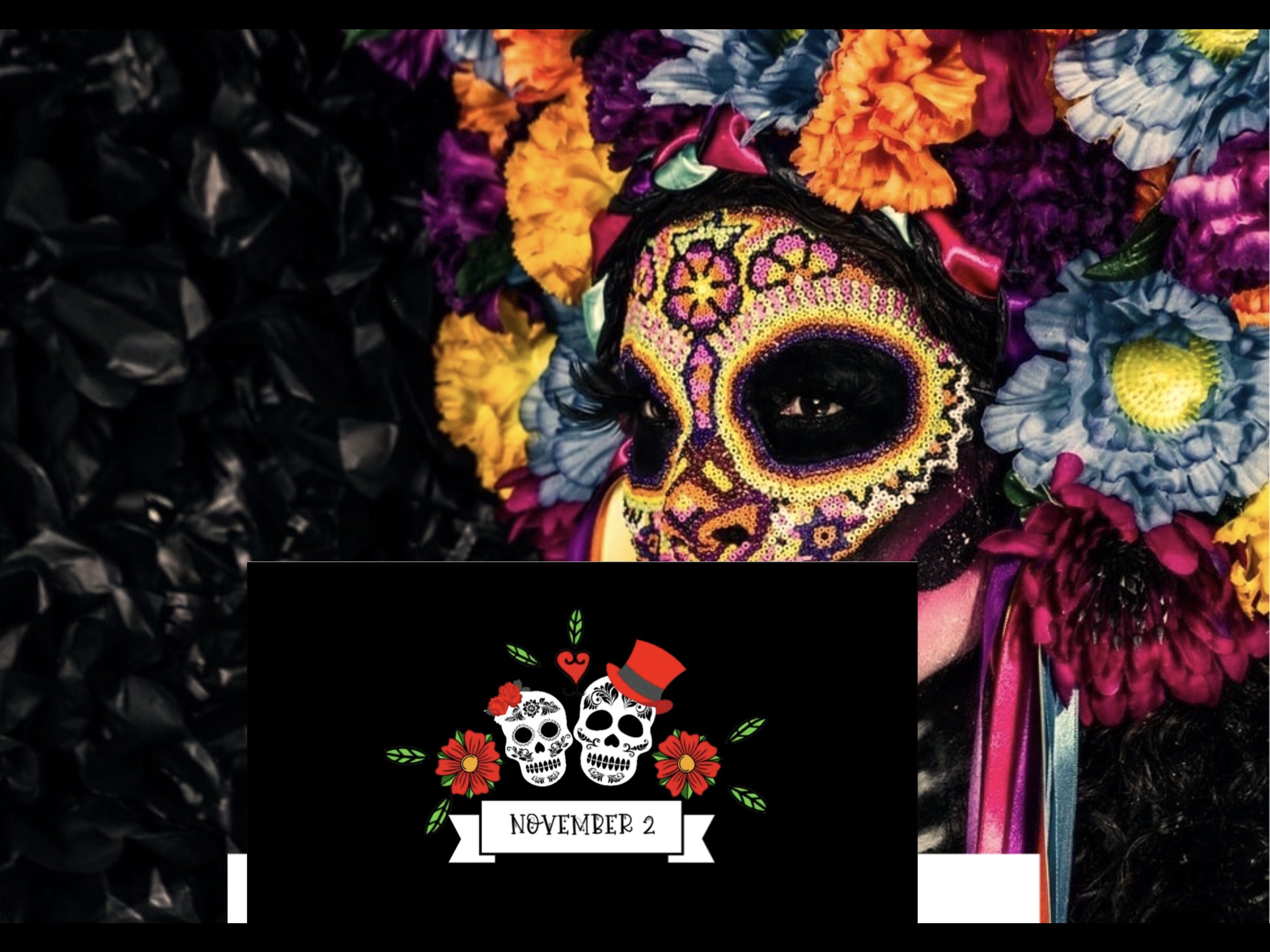

The calaveritas

emerged at the end of the nineteenth century and go hand in

hand with the illustrations published by José Guadalupe Posada, who is

credited with the creation of what is now known as “La Catrina”, the most

recognized symbol inside and outside Mexico of the Day of the Dead.

More In addition to the offerings and visits to the cemeteries, other practices have been added in recent years that reflect how

this festival has evolved generation after generation, giving rise, as UNESCO points out, to diverse popular expressions with

“different meanings and evocations according to the indigenous people, community or group that carry them out, in

the countryside or in the city.”

Perhaps the most globalized example of this evolution is the massive parade of catrinas that takes place in Mexico City after the

film “Spectre”, from the James Bond saga, presented a staging of a folklorized vision of the Day of the Dead.